On December 15, 2017, a House of Representatives and Senate Conference Committee released a unified version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This followed passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act by the House of Representatives on November 16, 2017, and by the Senate on December 2, 2017. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would reform the individual income tax code by lowering tax rates on wages, investment, and business income; broadening the tax base; and simplifying the tax code. The plan would lower the corporate income tax rate to 21 percent and move the United States from a worldwide to a territorial system of taxation.

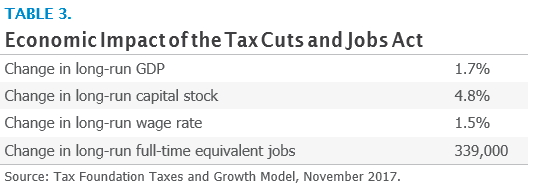

Our analysis1 finds that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would reduce marginal tax rates on labor and investment. As a result, we estimate that the plan would increase long-run GDP by 1.7 percent. The larger economy would translate into 1.5 percent higher wages and result in an additional 339,000 full- time equivalent jobs. Due to the larger economy and the broader tax base, the plan would generate $600 billion in additional permanent revenue over the next decade on a dynamic basis. Overall, the plan would decrease federal revenues by $1.47 trillion on a static basis and by $448 billion on a dynamic basis. The remaining difference is explained by temporary dynamic revenue growth from the bill’s numerous expiring provisions.

These results differ from our previous analysis of the original House version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the original Senate version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, due to the multitude of changes during each chamber’s markup process and agreements made during the conference committee.

Lowers most individual income tax rates, including the top marginal rate from 39.6 percent to 37 percent. Retains the current seven-bracket structure, but bracket widths are modified. (Table 1 and Table 2)

Note: The Head of Household filing status is retained, with a separate bracket schedule.

•Indexes tax brackets and other provisions by the chained CPI measure of inflation.

•Increases the standard deduction to $12,000 for single filers, $18,000 for heads of household, and $24,000 for joint filers in 2018 (compared to $6,500, $9,550, and $13,000 respectively under current law).

•Eliminates the personal exemption.

•Retains the charitable contribution deduction and limits the mortgage interest deduction to the first $750,000 in principal value. Limits the state and local tax deduction to a combined $10,000 for income, sales, and property taxes. Taxes paid or accrued in carrying on a trade or business are not limited.

•Limits or eliminates a number of other deductions.

•Expands the child tax credit from $1,000 to $2,000, while increasing the phaseout from $110,000 in current law to $400,000 married couples. The first $1,400 would be refundable.

•Effectively repeals the individual mandate penalty, by lowering the penalty amount to $0, effective January 1, 2019.

•Raises the exemption on the alternative minimum tax from $86,200 to $109,400 for married filers and increases the phaseout threshold to $1 million.

•The majority of individual income tax changes would be temporary, expiring on December 31, 2025. Several, such as the adoption of chained CPI and functional repeal of the individual mandate, would be permanent.

•Lowers the corporate income tax rate permanently to 21 percent, starting in 2018.

•Establishes a 20 percent deduction of qualified business income from certain pass-through businesses. Specific service industries, such as health, law, and professional services, are excluded. However, joint filers with income below $315,000 and other filers with income below $157,500 can claim the deduction fully on income from service industries. This provision would expire December 31, 2025.

•Allows full and immediate expensing of short-lived capital investments for five years. Increases the section 179 expensing cap from $500,000 to $1 million.

•Limits the deductibility of net interest expense to 30 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for four years, and 30 percent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) thereafter.

•Eliminates net operating loss carrybacks and limits carryforwards to 80 percent of taxable income.

•Eliminates the domestic production activities deduction (section 199) and modifies other provisions, such as the orphan drug credit and the rehabilitation credit.

•Enacts deemed repatriation of currently deferred foreign profits, at a rate of 15.5 percent for cash and cash-equivalent profits and 8 percent for reinvested foreign earnings.

•Moves to a territorial system with base erosion rules.

•Eliminates the corporate alternative minimum tax.

•Doubles the estate tax exemption from $5.6 million to $11.2 million, which expires on December 31, 2025. The exemption will increase with inflation.

According to the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would increase the long-run size of the U.S. economy by 1.7 percent (Table 3). The larger economy would result in 1.5 percent higher wages and a 4.8 percent larger capital stock. The plan would also result in 339,000 additional full-time equivalent jobs.

The larger economy and higher wages are due chiefly to the significantly lower cost of capital under the proposal, which reduces the corporate income tax rate and accelerates expensing of capital investment for short-lived assets.

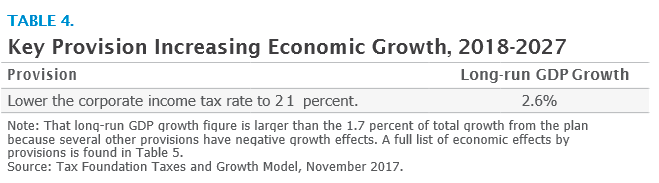

The long-run economic changes are generated by the corporate income tax rate cut. Table 4 below isolates the economic impact of this key provision that increases long-run economic growth.

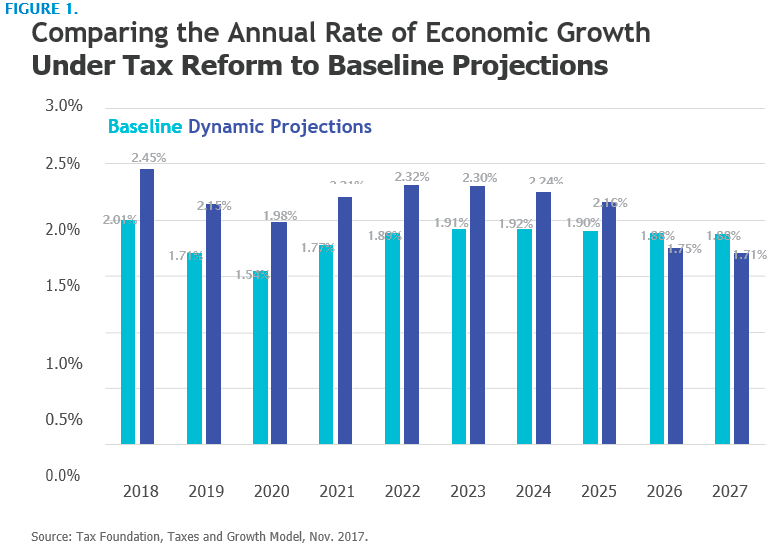

The growth of GDP under this plan, however, is not linear. In 2018, the first year of this tax plan, growth is projected to jump 0.44 percent above the current baseline projection as firms take advantage of the full and immediate expensing of equipment and the lower corporate income tax rate. These provisions encourage capital investment.

The initial spike in growth is reduced later during the decade, however, when growth falls slightly below the baseline. This is due to the temporary nature of many of these provisions. Economic growth is borrowed from the future, but the plan, in aggregate, still increases economic growth over the long run. The figure below illustrates this phenomenon.

Over the next decade, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would increase GDP by 2.86 percent over the current baseline forecasts, or an average of 0.29 percent per year. This means an increase of total GDP of approximately $5 trillion over the next decade, well exceeding the revenue lost by the plan.

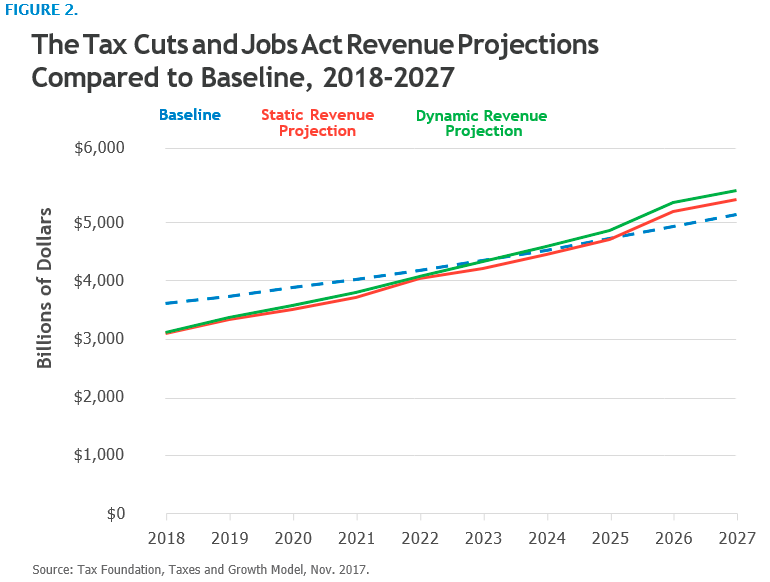

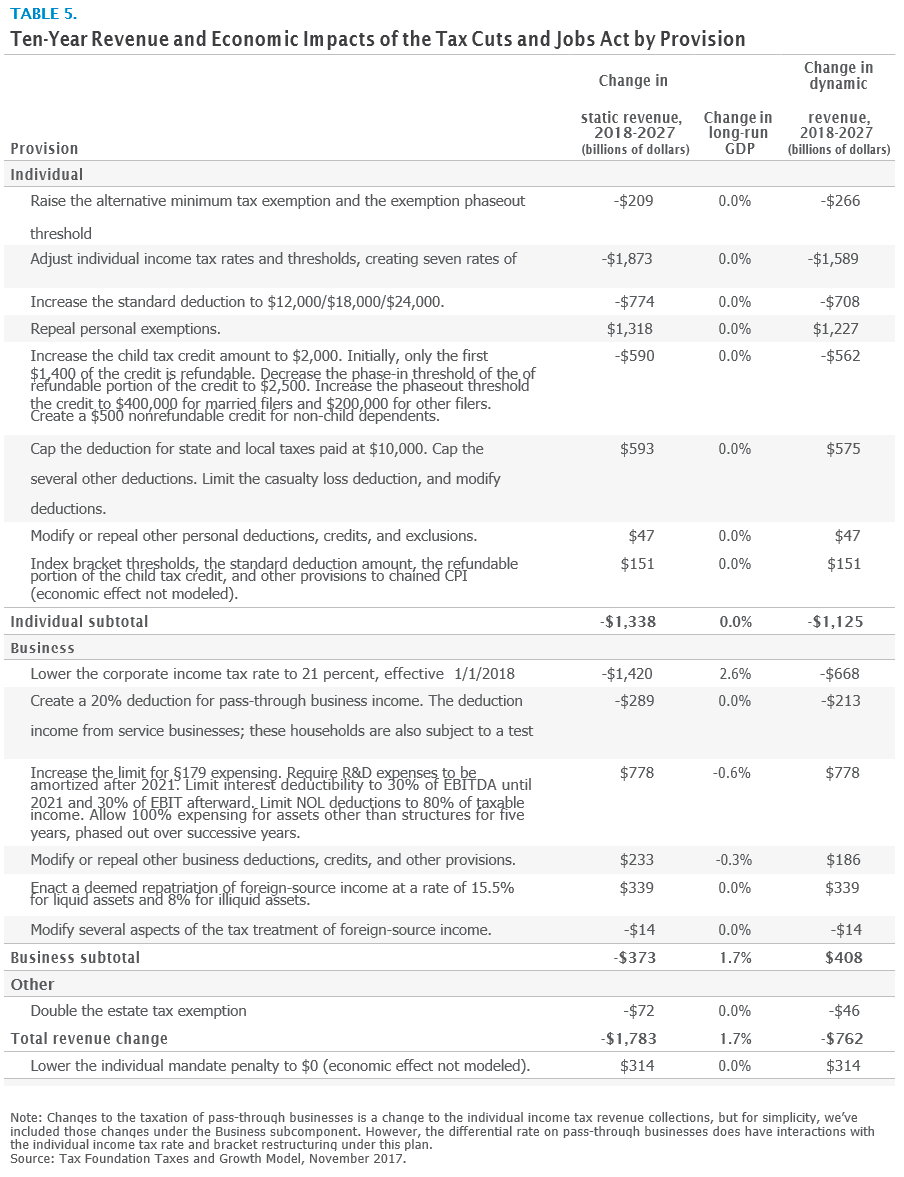

If fully implemented, the proposal would reduce federal revenue by $1.47 trillion over the next decade on a static basis (Figure 2) using a current law baseline. The plan would reduce individual income tax revenue, excluding the changes for noncorporate business tax filers, by $1.1 trillion over the next decade. Tax revenue from the corporate income tax and from taxation of pass-through business income would fall by $617 billion. The remainder of the revenue loss would be due to the doubling of the estate tax exemption, resulting in a revenue loss of $72 billion.

On a dynamic basis, this plan would generate an additional $600 billion in revenues, reducing the cost of the plan over the next decade. The larger economy would boost wages and thus broaden both the income and payroll tax base. As a result, the federal government would see a smaller revenue loss from personal tax changes, of $494 billion. The reduction in tax revenue from business changes would also be smaller on a dynamic basis, at $565 billion. The corporate tax revenue loss would be most significant in the short term because of the temporary expensing provision for short-lived assets, which would encourage more investment and result in businesses taking larger deductions for capital investments in the first five years of the plan.

The figure below compares static and dynamic revenue collection to the current law baseline. By the end of the decade, dynamic revenues have exceeded the baseline. In fact, dynamic revenues exceed the current law baseline in 2023, when the temporary expensing provisions expire, as the costs of the plan drop.

By 2024, dynamic revenue projections are back above the baseline projections, meaning that federal revenues would actually increase in those years when accounting for economic growth. In 2026, static revenue projections are also above the baseline projections, largely due to the expiration of many individual provisions. These results, however, should not be interpreted to mean that these tax changes are self-financing. Instead, they illustrate that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act includes a number of revenue offsets to reduce the overall cost of the tax rate cuts included in the plan.

The first large set of base broadeners is the elimination of a number of credits and deductions for individuals. Notably, the state and local tax deduction would be limited to a maximum deduction of $10,000 for income, sales, and property taxes (except as relates to business activity), and the mortgage interest deduction would be limited to the first $750,000 in principal value. The plan would also limit a number of deductions. These provisions would raise $640 billion over the next decade.

On the business side, the bill includes several base broadeners. It would limit the net interest deduction to 30 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for four years, and 30 percent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) thereafter, including for already originated loans. It would also limit or eliminate a number of business tax expenditures, such as the domestic production activities (section 199) deduction, the orphan drug credit, and the deduction for entertainment expenses. Repealing and limiting many of these expenditures would generate $1.0 trillion in revenue.

The largest source of revenue loss in the first decade would be the individual and corporate rate cuts. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would retain the current seven individual income tax brackets, but would modify both their widths and tax rates. The top marginal tax rate would fall from 39.6 percent under current law to 37 percent, with many other rates decreasing as well. The individual income tax rate changes, however, are temporary until December 31, 2025. This reduces the cost of the changes over the 10-year budget window, as they are only in effect for eight of the 10 years. These changes would reduce revenues by $1.9 trillion. The corporate income tax rate would fall from 35 percent to 21 percent on January 1, 2018, reducing revenues by $1.4 trillion. The plan would also provide many pass-through businesses with a 20 percent deduction for pass-through business income. Specified service business would be ineligible, except for households with taxable income below $157,500 for single filers and $315,000 for married filers. This provision reduces revenue by $289 billion.

Table 5 summarizes the revenue impacts, both static and dynamic, of each of the major provisions.

For many of these provisions, such as the individual income tax cuts, there is no long-term economic growth generated because they expire. However, they do provide some dynamic revenue for the period in which they are in place. For instance, the individual income tax rate cuts do not produce long-run economic growth, but do provide $284 billion in dynamic revenue. Individuals would take advantage of the lower marginal tax rates for the time that the tax cuts are in effect, temporarily increasing their labor force participation and their hours worked, but we would expect that the additional work effort would revert to its baseline level after the tax cuts expire.

Although the plan would reduce federal revenues by $1.47 trillion over the next 10 years, the plan would also have a smaller impact on revenues in the second decade. There are several provisions that contribute to the first decade’s higher transitional costs, including changes to expensing rules and inflation measures.

The plan would index tax brackets, the standard deduction, and other provisions to chained CPI rather than CPI. This provision would raise relatively little revenue in the short term, but would increase revenue over time as these two inflation indices diverge.

Moving in the opposite direction is the temporary nature of the majority of the individual income tax changes. Most of the individual tax changes expire on December 31, 2025. Only several provisions, such as the adoption of chained CPI and the functional repeal of the individual mandate, are permanent. The expiration of these provisions lowers the cost of the plan within the second decade, as they are no longer in effect. If those provisions are extended or made permanent in the future, the costs of the bill would be higher than stated in this paper.

Moving to temporary full expensing for short-lived assets would also reduce revenues in the first decade. Because this provision is currently slated to expire after five years, its impacts in the second decade are limited. However, any future changes to this provision, such as extending it or making it permanent, could impact revenues in the future.

The plan includes a major transitional revenue raiser, deemed repatriation. This proposal would tax corporations on their current deferred offshore profits and raise $339 billion over the next decade. We assume that this provision would only raise revenue in the first decade.

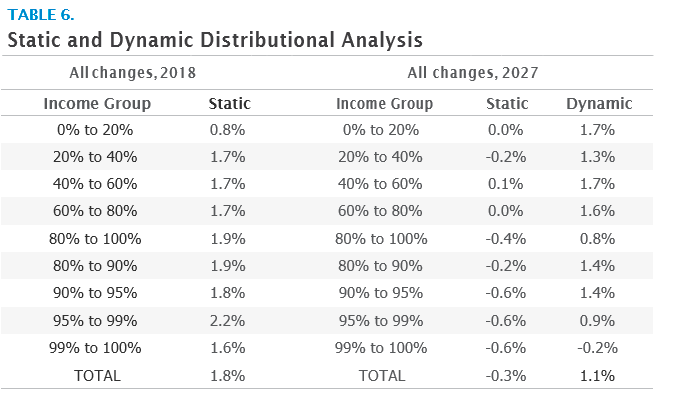

On a static basis, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would increase the after-tax incomes of taxpayers in every taxpayer group in 2018. The bottom 80 percent of taxpayers (those in the bottom four quintiles) would see an average increase in after-tax income ranging from 0.8 to 1.7 percent.

Taxpayers in the top 1 percent would see an increase in after-tax income on a static basis of 1.6 percent, driven by the lower pass-through tax rate and the lower corporate income tax.

By 2027, the distribution of the federal tax burden would look different, for several reasons. First, the bill includes temporary provisions, such as increased expensing for short-lived capital investments for businesses and the majority of the individual tax changes. Because these provisions would expire after 2025, taxpayers would not benefit from them in 2027. Second, by 2027 taxpayers would be subject to the effect of indexing bracket thresholds to chained CPI, which would reduce the benefit of the increased standard deduction and individual income tax cuts.

Additionally, unlike the methodology of the Joint Committee on Taxation, we do not distribute the functional repeal of the individual mandate. By dropping the individual mandate penalty to zero, JCT assumes that fewer individuals will purchase insurance, reducing the number of individuals, particularly among low-income households, that claim a premium tax credit to offset the cost of purchasing insurance.2 We did not distribute the individual mandate changes.

These distributional tables also do not reflect any transitional revenue effects from changes to depreciation under this plan.

Accounting for these factors, most groups of taxpayers on a static basis would still see a decrease in after-tax income, on average, in 2027. The bottom 80 percent of taxpayers would see an average increase in after-tax income ranging from -0.2 to 0.1 percent. The top 1 percent would see the largest decrease in after-tax income on a static basis, of -0.6 percent.

However, by 2027, the economic growth effects of the tax bill will have largely been realized. Taking these effects into account, taxpayers as a whole would see an increase in after-tax incomes of at least 1.1 percent. The bottom 80 percent of taxpayers would see their after-tax incomes increase from 0.8 to 1.7 percent. The top 1 percent of all taxpayers would see a decrease in after-tax income of -0.2 percent on a dynamic basis, largely due to chained CPI, the alternative minimum tax, and the net interest deduction limitation.

These dynamic results include the impact of both individual and corporate income tax changes on the U.S. economy. Static estimates assume that 25 percent of the cost of the corporate income tax is borne by labor. Dynamic estimates assume that 70 percent of the full burden of the corporate income tax is borne by labor, due to the negative effects of the tax on investment and wages.

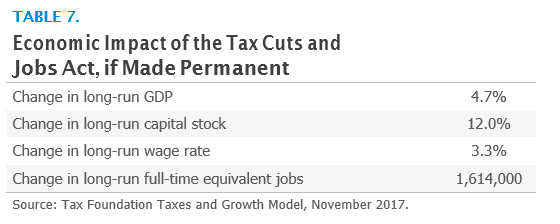

As discussed previously, many of the provisions of this tax bill would expire on December 31, 2025, to ensure the bill meets the requirements of the Senate’s Byrd Rule. We have also scored the plan as if the plan were made permanent. This change would increase the cost of the plan, but also increase the economic growth and dynamic revenue generated by the plan.

If the entire plan were enacted permanently, it would increase long-run GDP by 4.7 percent, raise wages by 3.3 percent, and create 1.6 million new full-time equivalent jobs. However, the cost of the bill would be $2.7 trillion on a static basis ($1.4 trillion on a dynamic basis) over the next decade. By 2027, the dynamic revenue projections would exceed the baseline revenue projections by $32 billion, with the trend continuing into the subsequent decade.

These changes would also have profound impacts on the distributional tables. While the distributional table in 2018 would be the same (as no provisions are expiring before 2018), taxpayers would see a dramatically higher increase in after-tax incomes in 2027 under a permanent tax plan.

On average, after-tax incomes would increase by 1.9 percent, with the bottom 80 percent seeing increases between 0.7 and 1.7 percent. The top 1 percent would see an increase of 2.5 percent.

After accounting for economic growth, after-tax incomes would increase by 6.5 percent on average, assuming the plan is made permanent. The bottom 80 percent would see increases between 5.8 and 6.6 percent, with the top 1 percent seeing an increase of 5.7 percent.

These distributional tables—similar to the ones above—do not, however, distribute the economic impacts of the functional repeal of the individual mandate.

On December 15, 2017, the Joint Committee on Taxation released a static estimate of the revenue effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.3 While preparing this report, the Tax Foundation relied in several instances on the Joint Committee’s estimates, particularly regarding tax provisions about which little public data exists. However, for most major provisions of the bill, the Tax Foundation estimated revenue effects using its own revenue model. On some provisions, the Tax Foundation model results were quite similar to those of the Joint Committee; for other provisions, the results diverged.

Overall, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that the plan would reduce federal revenue by $1.46 trillion between 2018 and 2027. This is a lower cost estimate than the Tax Foundation’s static score of $1.47 trillion. The Joint Committee on Taxation did not release a dynamic score of the plan.

Our static scores on individual income tax provisions varied significantly. The Tax Foundation’s higher estimate for the cost of consolidating and lowering individual tax rates may be because the Tax Foundation’s model utilizes taxpayer microdata from 2008, while the Joint Committee’s model may have access to more recent taxpayer data.

There are three primary sources of uncertainty in modeling the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: the significance of deficit effects, the timing of economic effects, and expectations regarding the extension of temporary provisions.

Some economic models assume that there is a limited amount of saving available to the United States to fund new investment opportunities when taxes on investment are reduced, and that when the federal budget deficit increases, the amount of available saving for private investment is “crowded out” by government borrowing, which reduces the long-run size of the U.S. economy. While past empirical work has found evidence of crowd-out, the estimated impact is usually small. Furthermore, global saving remains high, which may explain why interest rates remain low despite rising budget deficits. We assume that global saving is available to assist in the expansion of U.S. investment, and that a modest deficit increase will not meaningfully crowd out private investment in the United States.4

We are also forced to make certain assumptions about how quickly the economy would respond to lower tax burdens on investment. There is an inherent level of uncertainty here that could impact the timing of revenue generation within the budget window.

Finally, we assume that temporary tax changes will expire on schedule, and that business decisions will be made in anticipation of this expiration. To the extent that investments are made in the anticipation that temporary expensing provisions might be extended, economic effects could exceed our projections.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act represents a dramatic overhaul of the U.S. tax code. Our model results indicate that the plan would be pro-growth, boosting long-run GDP 1.7 percent and increasing the domestic capital stock by 4.8 percent. Wages, long stagnant, would increase 1.5 percent, while the reform would produce 339,000 jobs. These economic effects would have a substantial impact on revenues as well, as indicated by the plan’s significantly lower revenue losses under dynamic scoring.